This is a difficult question to answer because it depends on which features of the databases are used and when those features were introduced. SQL databases tend to be very strongly backwards-compatible so it's likely that SQLx will work with some very old versions.

TLS support is one of the features that ages most quickly with databases, since old SSL/TLS versions are deprecated over time as they become insecure due to weaknesses being discovered; this is especially important to consider when using RusTLS, as it only supports the latest TLS version for security reasons (see the question below mentioning RusTLS for details).

As a rule, however, we only officially support the range of versions for each database that are still actively maintained, and will drop support for versions as they reach their end-of-life.

- Postgres has a page to track these versions and give their end-of-life dates: https://www.postgresql.org/support/versioning/

- MariaDB has a similar list here (though it doesn't show the dates at which old versions were EOL'd): https://mariadb.com/kb/en/mariadb-server-release-dates/

- MySQL's equivalent page is more concerned with what platforms are supported by the newest and oldest maintained versions: https://www.mysql.com/support/supportedplatforms/database.html

- However, its Wikipedia page helpfully tracks its versions and their announced EOL dates: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MySQL#Release_history

- SQLite is easy as only SQLite 3 is supported and the current version depends on the version of the

libsqlite3-syscrate being used.

For each database and where applicable, we test against the latest and oldest versions that we intend to support. You can see the current versions being tested against by looking at our CI config: https://github.com/launchbadge/sqlx/blob/main/.github/workflows/sqlx.yml#L168

SQLx's MSRV is the second-to-latest stable release as of the beginning of the current release cycle (0.x.0).

It will remain there until the next major release (0.{x + 1}.0).

For example, as of the 0.8.0 release of SQLx, the latest stable Rust version was 1.79.0, so the MSRV for the

0.8.x release cycle of SQLx is 1.78.0.

This guarantees that SQLx will compile with a Rust version that is at least six weeks old, which should be plenty of time for it to make it through any packaging system that is being actively kept up to date.

We do not recommend installing Rust through operating system packages, as they can often be a whole year or more out-of-date.

*Minimum Supported Rust Version

I'm getting HandshakeFailure or CorruptMessage when trying to connect to a server over TLS using RusTLS. What gives?

To encourage good security practices and limit cruft, RusTLS does not support older versions of TLS or cryptographic algorithms

that are considered insecure. HandshakeFailure is a normal error returned when RusTLS and the server cannot agree on parameters for

a secure connection.

Check the supported TLS versions for the database server version you're running. If it does not support TLS 1.2 or greater, then you likely will not be able to connect to it with RusTLS.

The ideal solution, of course, is to upgrade your database server to a version that supports at least TLS 1.2.

- MySQL: has supported TLS 1.2 since 5.6.46.

- PostgreSQL: depends on the system OpenSSL version.

- MSSQL: TLS is not supported yet.

If you're running a third-party database that talks one of these protocols, consult its documentation for supported TLS versions.

If you're stuck on an outdated version, which is unfortunate but tends to happen for one reason or another, try switching to the corresponding

runtime-<tokio, async-std, actix>-native-tls feature for SQLx. That will use the system APIs for TLS which tend to have much wider support.

See the native-tls crate docs for details.

The CorruptMessage error occurs in similar situations and many users have had success with switching to -native-tls to get around it.

However, if you do encounter this error, please try to capture a Wireshark or tcpdump trace of the TLS handshake as the RusTLS folks are interested

in covering cases that trigger this (as it might indicate a protocol handling bug or the server is doing something non-standard):

rustls/rustls#893

Why can't I use DDL (e.g. CREATE TABLE, ALTER TABLE, etc.) with the sqlx::query*() functions or sqlx::query*!() macros?

These questions can all be answered by a thorough explanation of prepared statements. Feel free to skip the parts you already know.

Back in the day, if a web application wanted to include user input in a SQL query, a search parameter for example, it had no choice but to simply format that data into the query. PHP applications used to be full of snippets like this:

/* Imagine this is user input */

$city = "Munich";

/* $query = "SELECT country FROM city WHERE name='Munich'" */

$query = sprintf("SELECT country FROM city WHERE name='%s'", $city);

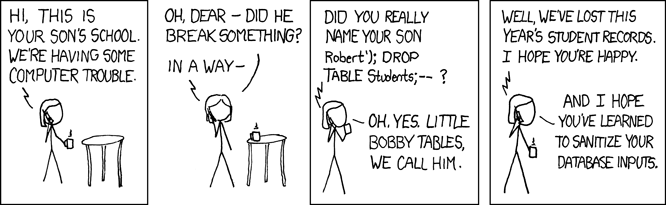

$result = $mysqli->query($query);However, this leaves the application vulnerable to SQL injection attacks, because it's trivial to craft an input string that will terminate the existing query and begin a new one, and the database won't know the difference and will execute both. As illustrated in the famous XKCD #327:

The fictional school's student database application might have contained a query that looked like this:

$student_name = "Robert');DROP TABLE Students;--"

$query = sprintf("INSERT INTO Students (name) VALUES ('%s')", $student_name);

$result = $mysqli->query($query);When formatted into the middle of this query, the maliciously crafted input string closes the quotes and finishes the statement (Robert');),

then starts another one with the nefarious payload (DROP TABLE Students;), and causes the rest of the original query to be ignored by starting a SQL comment (--).

Thus, the database server sees, and executes, three separate statements like so:

INSERT INTO Students(firstname) VALUES ('Robert');

DROP TABLE Students;

--');And thus the school has lost this year's student records (at least they had last years' backed up?).

The original mitigation for this attack was to make sure that any untrustworthy user input was properly escaped (or "sanitized"),

and many frameworks provided utility functions for this, such as PHP's mysqli::real_escape_string() (not to be confused with the obsolete mysql_real_escape_string() or mysql_escape_string()).

These would prefix any syntactically significant characters (in this case, quotation marks) with a backslash, so it's less likely to affect the database server's interpretation of the query:

$student_name = $mysqli->real_escape_string("Robert');DROP TABLE Students;--");

/*

Everything is okay now as the dastardly single-quote has been inactivated by the backslash:

"INSERT INTO Students (name) VALUES ('Robert\');DROP TABLE Students;--');"

*/

$query = sprintf("INSERT INTO Students (name) VALUES ('%s')", $student_name);The database server sees the backslash and knows that the single-quote is part of the string content, not its terminating character.

However, this was something that you still had to remember to do, making it only half a solution. Additionally, properly escaping the string requires knowledge of the current character set of the connection which is why the mysqli object is a required parameter

(or the receiver in object-oriented style). And you could always just forget to wrap the string parameter in quotes ('%s') in the first place, which these wouldn't help with.

Even when everything is working correctly, formatting dynamic data into a query still requires the database server to re-parse and generate a new query plan with every new variant--caching helps, but is not a silver bullet.

These solve both problems (injection and re-parsing) by completely separating the query from any dynamic input data.

Instead of formatting data into the query, you use a (database-specific) token to signify a value that will be passed separately:

-- MySQL

INSERT INTO Students (name) VALUES(?);

-- Postgres and SQLite

INSERT INTO Students (name) VALUES($1);The database will substitute a given value when executing the query, long after it's finished parsing it.

The database will effectively treat the parameter as a variable.

There is, by design, no way for a query parameter to modify the SQL of a query,

unless you're using some exec()-like SQL function that lets you execute a string as a query,

but then hopefully you know what you're doing.

In fact, parsing and executing prepared statements are explicitly separate steps in pretty much every database's protocol, where the query string, without any values attached, is parsed first and given an identifier, then a separate execution step simply passes that identifier along with the values to substitute.

The response from the initial parsing often contains useful metadata about the query, which SQLx's query macros use to great effect (see "How do the query macros work under the hood?" below).

Unfortunately, query parameters do not appear to be standardized, as every database has a different syntax. Look through the project for specific examples for your database, and consult your database manual about prepared statements for more information.

The syntax SQLite supports is effectively a superset of many databases' syntaxes, including MySQL and Postgres. To simplify our examples, we use the same syntax for Postgres and SQLite; though SQLite's syntax technically allows alphanumeric identifiers, that's not currently exposed in SQLx, and it's expected to be a numeric 1-based index like Postgres.

Some databases, like MySQL and PostgreSQL, may have special statements that let the user explicitly create and execute prepared statements (often PREPARE and EXECUTE, respectively),

but most of the time an application, or library like SQLx, will interact with prepared statements using specialized messages in the database's client/server protocol.

Prepared statements created through this protocol may or may not be accessible using explicit SQL statements, depending on the database flavor.

Since the dynamic data is handled separately, an application only needs to prepare a statement once, and then it can execute it as many times as it wants with all kinds of different data (at least of the same type and number). Prepared statements are generally tracked per-connection, so an application may need to re-prepare a statement several times over its lifetime as it opens new connections. If it uses a connection pool, ideally all connections will eventually have all statements already prepared (assuming a closed set of statements), so the overhead of parsing and generating a query plan is amortized.

Query parameters are also usually transmitted in a compact binary format, which saves bandwidth over having to send them as human-readable strings.

Because of the obvious security and performance benefits of prepared statements, the design of SQLx tries to make them as easy to use and transparent as possible.

The sqlx::query*() family of functions, as well as the sqlx::query*!() macros, will always prefer prepared statements. This was an explicit goal from day one.

SQLx will never substitute query parameters for values on the client-side, it will always let the database server handle that. We have concepts for making certain usage patterns easier,

like expanding a dynamic list of parameters (e.g. ?, ?, ?, ?, ...) since MySQL and SQLite don't really support arrays, but will never simply format data into a query implicitly.

Our pervasive use of prepared statements can cause some problems with third-party database implementations, e.g. projects like CockroachDB or PGBouncer that support the Postgres protocol but have their own semantics.

In this case, you might try setting .persistent(false) before executing a query, which will cause the connection not to retain

the prepared statement after executing it.

Not all SQL statements are allowed in prepared statements, either.

As a general rule, DML (Data Manipulation Language, i.e. SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE) is allowed while DDL (Data Definition Language, e.g. CREATE TABLE, ALTER TABLE, etc.) is not.

Consult your database manual for details.

To execute DDL requires using a different API than query*() or query*!() in SQLx.

Ideally, we'd like to encourage you to use SQLx's built-in support for migrations (though that could be better documented, we'll get to it).

However, in the event that isn't feasible, or you have different needs, you can execute pretty much any statement,

including multiple statements separated by semicolons (;), by directly invoking methods of the Executor trait

on any type that implements it, and passing your query string, e.g.:

use sqlx::postgres::PgConnection;

use sqlx::Executor;

let mut conn: PgConnection = connect().await?;

conn

.execute(

"CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS StudentContactInfo (student_id INTEGER, person_name TEXT, relation TEXT, phone TEXT);\

INSERT INTO StudentContactInfo (student_id, person_name, relation, phone) \

SELECT student_id, guardian_name, guardian_relation, guardian_phone FROM Students;\

ALTER TABLE Students DROP guardian_name, guardian_relation, guardian_phone;"

)

.await?;This is also pending a redesign to make it easier to discover and utilize.

In the future SQLx will support binding arrays as a comma-separated list for every database, but unfortunately there's no general solution for that currently in SQLx itself. You would need to manually generate the query, at which point it cannot be used with the macros.

However, in Postgres you can work around this limitation by binding the arrays directly and using = ANY():

let db: PgPool = /* ... */;

let foo_ids: Vec<i64> = vec![/* ... */];

let foos = sqlx::query!(

"SELECT * FROM foo WHERE id = ANY($1)",

// a bug of the parameter typechecking code requires all array parameters to be slices

&foo_ids[..]

)

.fetch_all(&db)

.await?;Even when SQLx gains generic placeholder expansion for arrays, this will still be the optimal way to do it for Postgres, as comma-expansion means each possible length of the array generates a different query (and represents a combinatorial explosion if more than one array is used).

Note that you can use any operator that returns a boolean, but beware that != ANY($1) is not equivalent to NOT IN (...) as it effectively works like this:

lhs != ANY(rhs) -> false OR lhs != rhs[0] OR lhs != rhs[1] OR ... lhs != rhs[length(rhs) - 1]

The equivalent of NOT IN (...) would be != ALL($1):

lhs != ALL(rhs) -> true AND lhs != rhs[0] AND lhs != rhs[1] AND ... lhs != rhs[length(rhs) - 1]

Note that ANY using any operator and passed an empty array will return false, thus the leading false OR ....

Meanwhile, ALL with any operator and passed an empty array will return true, thus the leading true AND ....

See also: Postgres Manual, Section 9.24: Row and Array Comparisons

Like the above, SQLx currently does not support this in the general case right now but will in the future.

However, Postgres also has a feature to save the day here! You can pass an array to UNNEST() and

it will treat it as a temporary table:

let foo_texts: Vec<String> = vec![/* ... */];

sqlx::query!(

// because `UNNEST()` is a generic function, Postgres needs the cast on the parameter here

// in order to know what type to expect there when preparing the query

"INSERT INTO foo(text_column) SELECT * FROM UNNEST($1::text[])",

&foo_texts[..]

)

.execute(&db)

.await?; UNNEST() can also take more than one array, in which case it'll treat each array as a column in the temporary table:

// this solution currently requires each column to be its own vector

// in the future we're aiming to allow binding iterators directly as arrays

// so you can take a vector of structs and bind iterators mapping to each field

let foo_texts: Vec<String> = vec![/* ... */];

let foo_bools: Vec<bool> = vec![/* ... */];

let foo_ints: Vec<i64> = vec![/* ... */];

let foo_opt_texts: Vec<Option<String>> = vec![/* ... */];

let foo_opt_naive_dts: Vec<Option<NaiveDateTime>> = vec![/* ... */]

sqlx::query!(

"

INSERT INTO foo(text_column, bool_column, int_column, opt_text_column, opt_naive_dt_column)

SELECT * FROM UNNEST($1::text[], $2::bool[], $3::int8[], $4::text[], $5::timestamp[])

",

&foo_texts[..],

&foo_bools[..],

&foo_ints[..],

// Due to a limitation in how SQLx typechecks query parameters, `Vec<Option<T>>` is unable to be typechecked.

// This demonstrates the explicit type override syntax, which tells SQLx not to typecheck these parameters.

// See the documentation for `query!()` for more details.

&foo_opt_texts as &[Option<String>],

&foo_opt_naive_dts as &[Option<NaiveDateTime>]

)

.execute(&db)

.await?;Again, even with comma-expanded lists in the future this will likely still be the most performant way to run bulk inserts

with Postgres--at least until we get around to implementing an interface for COPY FROM STDIN, though

this solution with UNNEST() will still be more flexible as you can use it in queries that are more complex

than just inserting into a table.

Note that if some vectors are shorter than others, UNNEST will fill the corresponding columns with NULLs

to match the longest vector.

For example, if foo_texts is length 5, foo_bools is length 4, foo_ints is length 3, the resulting table will

look like this:

| Row # | text_column |

bool_column |

int_column |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | foo_texts[0] |

foo_bools[0] |

foo_ints[0] |

| 2 | foo_texts[1] |

foo_bools[1] |

foo_ints[1] |

| 3 | foo_texts[2] |

foo_bools[2] |

foo_ints[2] |

| 4 | foo_texts[3] |

foo_bools[3] |

NULL |

| 5 | foo_texts[4] |

NULL |

NULL |

See Also:

- Postgres Manual, Section 7.2.1.4: Table Functions

- Postgres Manual, Section 9.19: Array Functions and Operators

The macros support an offline mode which saves data for existing queries to a .sqlx directory,

so the macros can just read those instead of talking to a database.

See the following:

To keep .sqlx up-to-date you need to run cargo sqlx prepare before every commit that

adds or changes a query; you can do this with a Git pre-commit hook:

$ echo "cargo sqlx prepare > /dev/null 2>&1; git add .sqlx > /dev/null" > .git/hooks/pre-commit Note that this may make committing take some time as it'll cause your project to be recompiled, and

as an ergonomic choice it does not block committing if cargo sqlx prepare fails.

We're working on a way for the macros to save their data to the filesystem automatically which should be part of SQLx 0.7,

so your pre-commit hook would then just need to stage the changed files. This can be enabled by creating a directory

and setting the SQLX_OFFLINE_DIR environment variable to it before compiling.

However, this behaviour is not considered stable and it is still recommended to use cargo sqlx prepare.

The macros work by talking to the database at compile time. When a(n) SQL client asks to create a prepared statement from a query string, the response from the server typically includes information about the following:

- the number of bind parameters, and their expected types if the database is capable of inferring that

- the number, names and types of result columns, as well as the original table and columns names before aliasing

In MySQL/MariaDB, we also get boolean flag signaling if a column is NOT NULL, however

in Postgres and SQLite, we need to do a bit more work to determine whether a column can be NULL or not.

After preparing, the Postgres driver will first look up the result columns in their source table and check if they have

a NOT NULL constraint. Then, it will execute EXPLAIN (VERBOSE, FORMAT JSON) <your query> to determine which columns

come from half-open joins (LEFT and RIGHT joins), which makes a normally NOT NULL column nullable. Since the

EXPLAIN VERBOSE format is not stable or completely documented, this inference isn't perfect. However, it does err on

the side of producing false-positives (marking a column nullable when it's NOT NULL) to avoid errors at runtime.

If you do encounter false-positives please feel free to open an issue; make sure to include your query, any relevant

schema as well as the output of EXPLAIN (VERBOSE, FORMAT JSON) <your query> which will make this easier to debug.

The SQLite driver will pull the bytecode of the prepared statement and step through it to find any instructions that produce a null value for any column in the output.

Take a moment and think of the effort that would be required to do that.

To implement this for a single database driver, SQLx would need to:

- know how to parse SQL, and not just standard SQL but the specific dialect of that particular database

- know how to analyze and typecheck SQL queries in the context of the original schema

- if inferring schema from migrations it would need to simulate all the schema-changing effects of those migrations

This is effectively reimplementing a good chunk of the database server's frontend,

and maintaining and ensuring correctness of that reimplementation,

including bugs and idiosyncrasies,

for the foreseeable future,

for every database we intend to support.

Even Sisyphus would pity us.

Docs.rs doesn't have access to your database, so it needs to be provided prepared queries in a .sqlx directory and be instructed to set the SQLX_OFFLINE environment variable to true while compiling your project. Luckily for us, docs.rs creates a DOCS_RS environment variable that we can access in a custom build script to achieve this functionality.

To do so, first, make sure that you have run cargo sqlx prepare to generate a .sqlx directory in your project.

Next, create a file called build.rs in the root of your project directory (at the same level as Cargo.toml). Add the following code to it:

fn main() {

// When building in docs.rs, we want to set SQLX_OFFLINE mode to true

if std::env::var_os("DOCS_RS").is_some() {

println!("cargo:rustc-env=SQLX_OFFLINE=true");

}

}